Is the Paris climate agreement even achievable?

Te Whanganui a Tara - In the fight against climate change, it is becoming clear the world must not only reduce overall emissions but also actively remove carbon from the atmosphere.

To do so, global efforts will be needed to scale-up, improve and cut costs of technologies that already exist.

This is particularly important, as hard-to-abate sectors like aviation, steel and cement are likely to reach net-zero after the target date of the 2015 Paris climate agreement, 2050.

New Zealand has climbed just two places in this year's CCPI global rankings to 33rd, putting it among the medium-performing countries. The country shows a mixed performance across the CCPI categories, with a low rating in energy use, very low in ghg emissions, medium in climate policy, and high in renewable energy.

He Pou a Rangi NZ Climate Change Commission, led by Dr Rod Carr, says to achieve a cleaner, greener, healthier and more sustainable future, no emission reduction is too small or too soon

Carbon dioxide is critical to the atmosphere. It traps the sun’s heat, and without it our planet would be impossibly cold.

But human activities principally burning fossil fuels have increased CO2 levels by around 50 percent, from 270 parts per million (ppm) at the dawn of the industrial revolution to 415 ppm today.

The last time atmospheric CO2 levels were this high was more than three million years ago. What concerns scientists is the acceleration in emissions, which over the past 60 years has been about 100 times faster than previous natural increases, such as at the end of the last ice age.

Since the Paris Agreement in 2015, the idea of a pathway limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels has become paramount.

To have even a chance of hitting this target, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions need to peak by 2025 at the latest and be reduced by 43 percent by 2030, achieving net-zero no later than 2050.

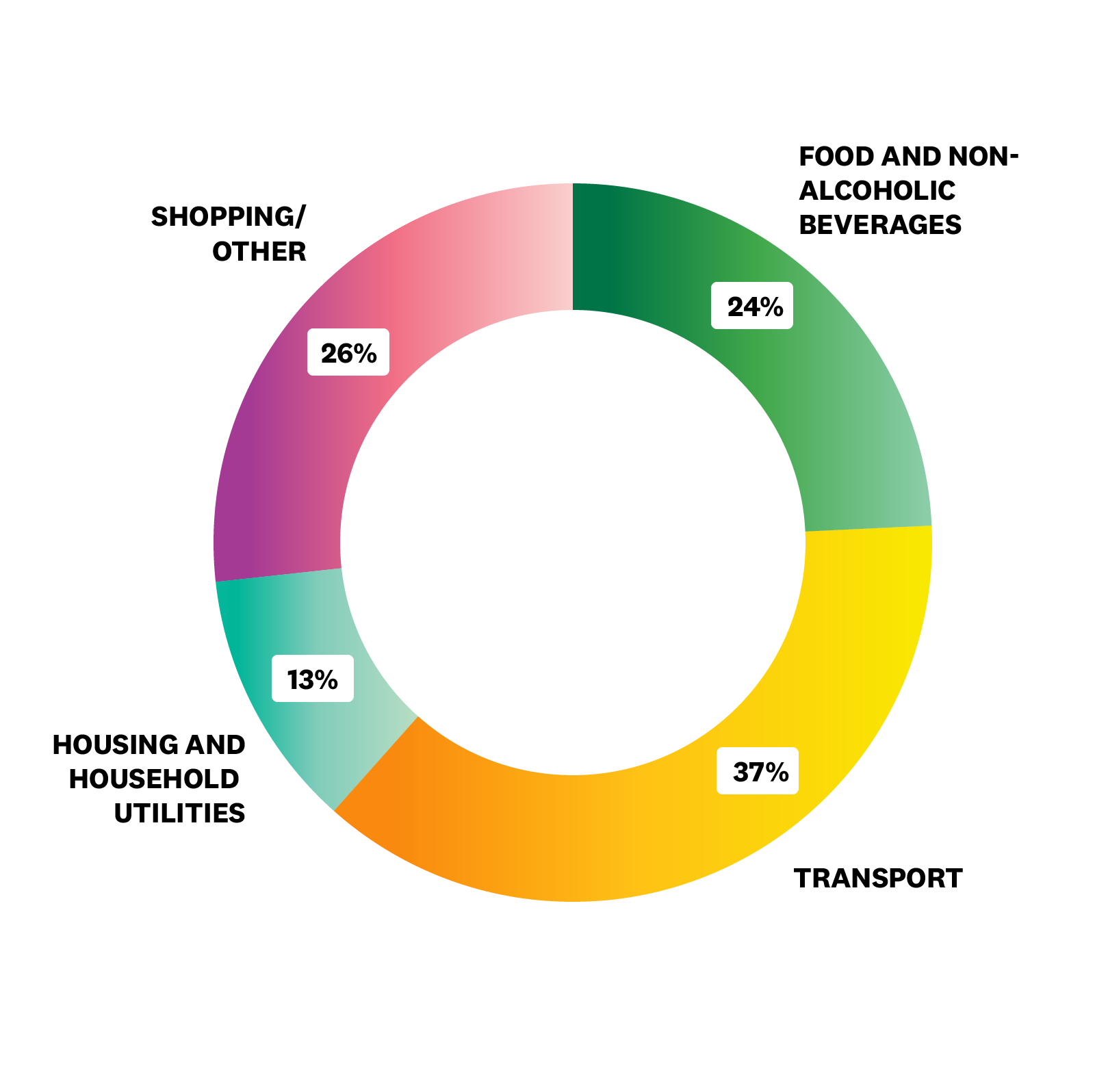

The great majority of these reductions must come from decarbonising industries, agriculture and lifestyles.

But despite efforts to decarbonise human activities, carbon dioxide removal, or CDR, will play a vital role, for three reasons. First, it is extremely difficult to fully decarbonize some essential but hard to abate industrial sectors, such as long-range aviation, cement and steel.

Second, the Earth system itself is emitting more greenhouse gases as global warming continues to increase. Third, we need to undo legacy emissions from the past, as well as remove present and future unabated emissions to prevent an otherwise likely overshoot of the 1.5°C target.

The world cannot afford to wait and see if CDR will be necessary. We must start building the necessary capacity right now to actively remove CO2 from the atmosphere, in parallel with not instead of doubling down on decarbonisation efforts.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change CDR is a key element in scenarios likely to limit warming to 2 [degrees] C or lower, regardless of whether global emissions reach near-zero, net-zero or net-negative levels.

Put simply the way the world is currently heading with CO2 mitigation, it is unlikely to reach global net-zero by 2050 and limit global warming to 1.5°C without scaling up CDR technologies to deliver billions of metric tonnes of removals every year.

Lisa was born in Auckland at the start of the 1970s, living in a small campsite community on the North Shore called Browns Bay. She spent a significant part of her life with her grandparents, often hanging out at the beaches. Lisa has many happy memories from those days at Browns Bay beach, where fish were plentiful on the point and the ocean was rich in seaweed. She played in the water for hours, going home totally “sun-kissed.” “An adorable time to grow up,” Lisa tells me.

Lisa enjoyed many sports; she was a keen tennis player and netballer, playing in the top teams for her age right up until the family moved to Wellington. Lisa was fifteen years old, which unfortunately marked the end of her sporting career. Local teams were well established in Wellington, and her attention was drawn elsewhere.